Building a Solid Narrative Foundation for a Video Game: Lessons Learned

A behind the scenes look at my games narrative. A retrospective on how to build a solid foundation for games narratives during production, and focusing on player read text.

For the last three months I’ve been working on a video game prototype with some classmates for UCSC. The game project at the current moment is an Action/Adventure game where you destroy robots. The game takes place on a space station completely inhabited by hostile robots, the main character crash lands inside the station and is saved by a weapon that has the mind of a dog inside of it. Since your ship is destroyed your goal is to escape the station, and survive the hostile environment. There are a lot more narrative points that I’ve skipped, but that is the gist of it.

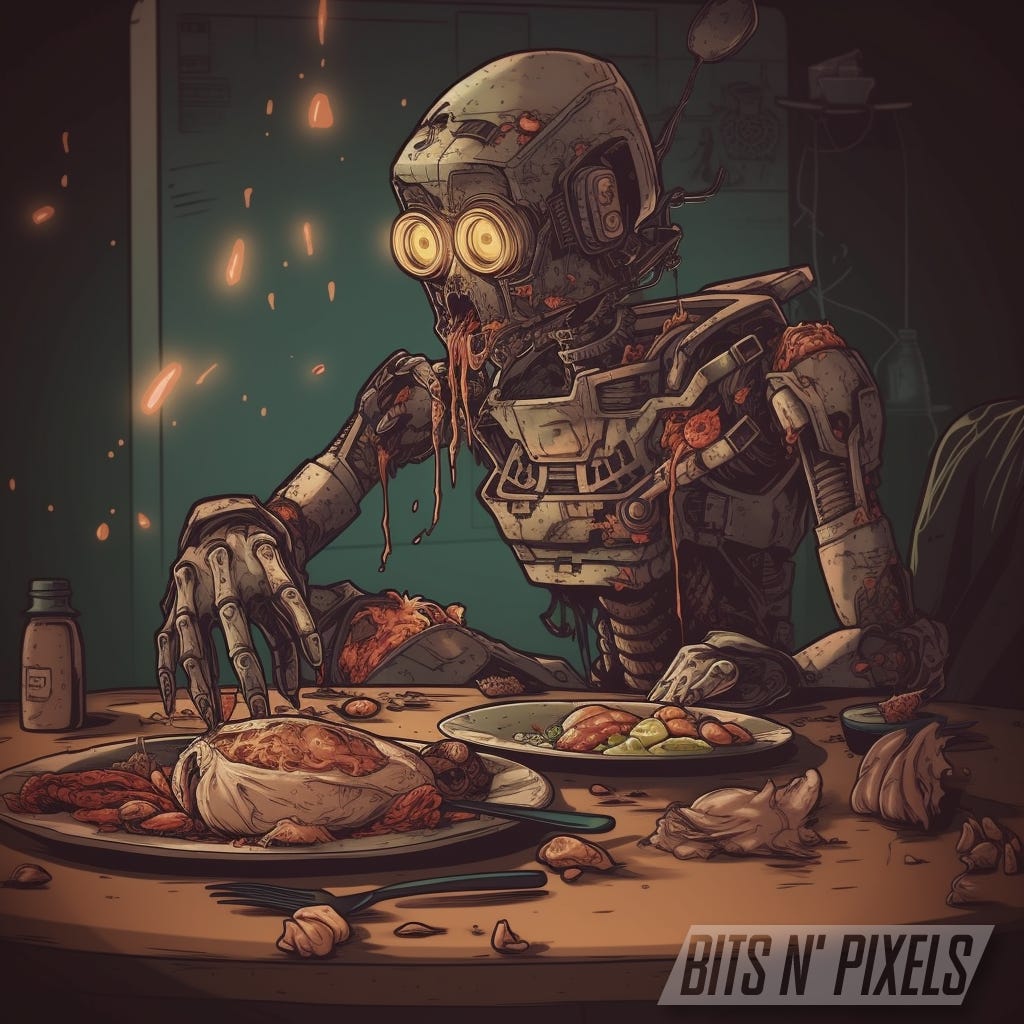

The inspiration for the narrative came from books like Infinite, We are Many we are Bob, and The Singularity trap. Of course among tons of other things that I’ve forgotten at the present moment. I’m a huge sci-fi fan and have been reading it for years, also as you can probably tell I’m a huge Dennis E. Taylor fan. Assuming my “Bacon Number” is low one day my writings may end up in front of him and I’ll get the chance to meet him. That would be cool. In any event, The main inspiration I had for the narrative was a flip of the Bob books. What if a robot didn’t want to be a robot anymore.

I had this very vivid image of a man trapped in a robotic non-humanoid body attempt to smash food into what it hysterically thinks could be a mouth. Burning with the desire to be mortal, but trapped in a mechanical body. I’m definitely not the first person to think this, but screw it this is my take on it. That eventually blossomed into a lot of ideas that I’m not totally sure go together, but I’ll be damned if I wasn’t going to give a shot. I had some design requirements from the programming team that they wanted the main mechanic to involve a sword with the brain of a dog. Originally the demo was going to be a roguelike so there needed to be a narrative reason for the player to A: not be killed when defeated, and B: why the levels were changing. Finally the weapon was going to be modular, and you got modules from defeating enemies. My personal goal was for the narrative to work around the game mechanics so we weren’t sacrificing anything, but to still allow the narrative to inform the game mechanics where needed.

Writing narrative for a game feels a lot like writing a manual for a car while the team is still deciding if they would rather have it be an airplane or a skateboard instead. As I said in my other post about creativity the goal really is just to have something and get it wrong. It will always be wrong. Embrace the chaos, make a mess. Since our game was so systematic I really had no idea what kind of info the narrative would even be delivered to the player in. The developers weren’t too interested in implementing narrative tools till the very end of the project, and most of them barely wanted text in the game. Which meant that I was doing most of the work behind the scenes. It was very messy, but I think it worked out well. I would leave and think about stuff that made sense for the game, then we would talk about it at our meetings and despite not having any actual text the gameplay programmers still took the new information into account while designing.

So lets talk about what ended up in the final game. I solved the problems listed above with the idea that the station was controlled by an AI that had total control over the station and it’s layout. The AI was a former human who, through scientific testing, was turned into the AI running the ship. Likewise the sword the player eventually finds, and binds with was cloned from his dog. One of the few remaining dogs in “future land.” The station was created under the guise of extending human life extra-terrestrially but in actuality was testing the program to turn people into robots and utilize their brains as AI. Dogs were the perfect candidate for weapons considering their loyalty and trainability towards people. However the main AI man running the station was unhappy about being turned into an AI and so they sabotaged the water system on the station destroying the stations life support. This forced all the people on the station to either convert to AI or starve to death. However the AI had also modified the AI transfer program in order to be able to control the newly formed robot people. The robots each would be equipped for different self-sustaining tasks on the station which are the modules that are used against the player, and thus the player can use back against the robots.

The modules that the player picks up exist along a timeline from “Things sent at the launch of the station” which are written very bureaucratically. I always get a kick writing these. There is something so funny about writing what qualifies confetti at a birthday party. Then there’s experimental weapons developed after the launch of the station. After that are weapons hack-need together by human resistance, and weapons designed by the AI to fight the resistance (which wouldn’t have accessible documentation for the player to read).

All in all that felt like a really solid base to start building a video-game narrative from. You can have a really solid base planned out, but if the player never sees any of it then does it even exist? The answer is no, it does not exist. In my opinion on this particular project I spent too much time planning. As a writer its hard to really understand the narrative and what happened without writing out text that someone is actually supposed to see. Even if it ends up getting changed, you have to lay a foundation. Write text that will be re-written. So when the level designer gave me the final level layout for our prototype that was when the narrative actually started to take shape.

I took the protagonist and just walked through the levels with a curious eye without talking to the level designer. What are these things? What would this room be used for? As I walked through I imaged a world with people in it. What would they be doing? What would they be saying to each other, and how could they have left it so that the player sees that information. The designers effectively left me with text boxes that I could leave around the level which I am more than happy with.

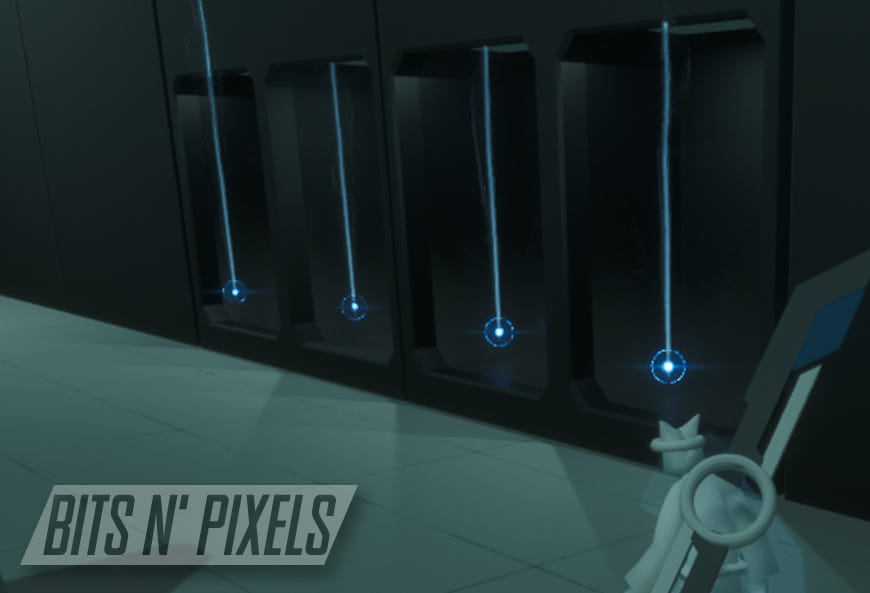

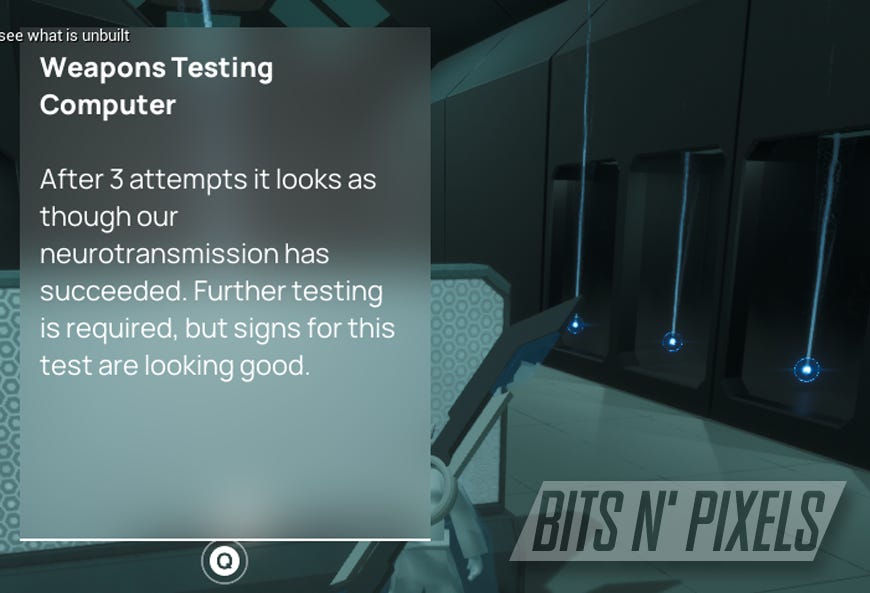

I started with the experimental weapons lab. How do I communicate the process of shoving a dog’s brain into an AI? Well there had to be some other dogs that were used and died as a part of the process right? These windows look like they could be memorials to the other dogs. I called the dog Laika for being the first animal to transition from biological to mechanical. I created the memorials for Liaka 1 through 3 and left a space for a 4th but indicated at another terminal hinting at success on this last attempt. Hopefully communicating to the player that the “sword” you are using is really the 4th attempt! This was a great stepping stone. I used this process to fill out almost every question I had about the space I was given. Large open space with trusses. That’s the “Large Object construction site.” Area with lots of tanks and tubes, obviously that’s the “Liquid Recycling Lab” which always needs people watching it because of how important that would be to a space station.

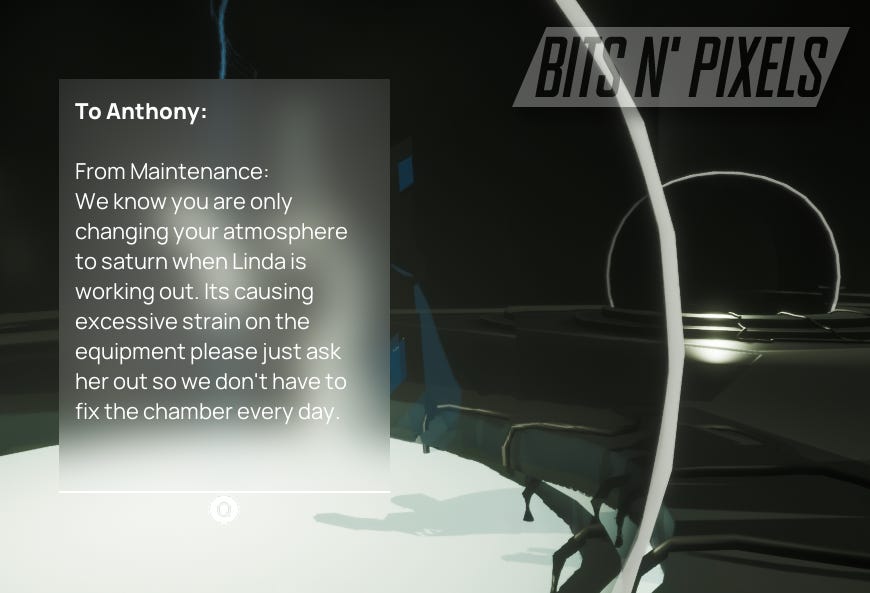

I worked from general to specific where I could. There was a room labelled “Gym” which was very futuristic looking, and came very pre-defined. The gym contained little terminals connected to futuristic looking orbs. Obviously those are atmospheric simulation chambers for exercising. Well, what state would those chambers be left in? Some people would have their chambers set to earth, sure. But wouldn’t there be some guy who would set his gravity to Saturn to show off whenever a girl comes in. Ok but how does the player find this out? What if maintenance left a secret note that the player can find telling that guy to just ask the girl out because he’s putting excessive strain on the equipment.

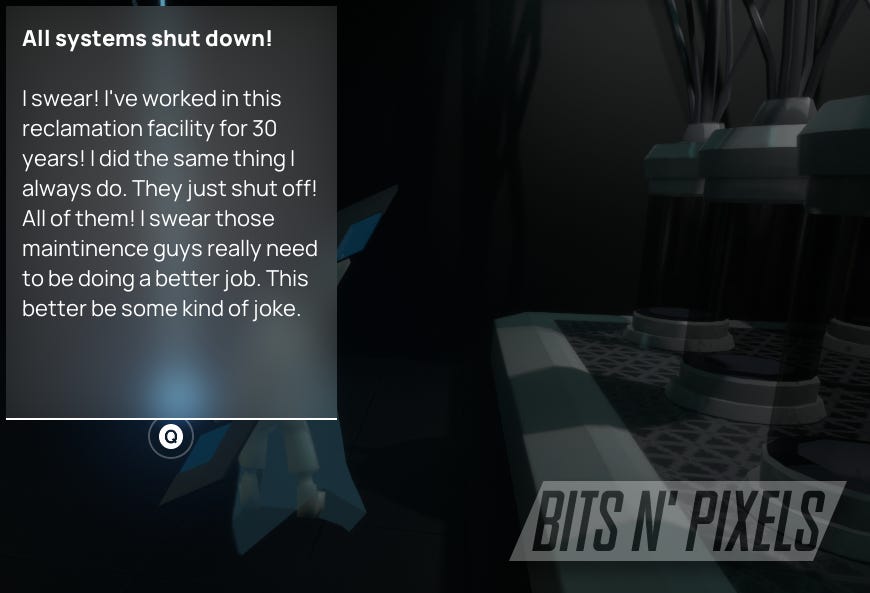

From there I was able to work those characters that I had created in those small moments into other places. I did multiple passes through the station as new information came to me, correcting old info, and adding info from multiple time periods so the player is not just handed info linearly. They slowly uncover the tragedy of the station and work backwards from “station is destroyed and overrun with robots.”

Overall I’m very happy with what I was able to produce. I’m always so happy with the level of character I’m able to inject into something. Like yeah this was a station with people on it, who did things. People left secret notes on walls, love letters, “yo mama jokes”, blocked emergency calls. They lived their lives here and I get to tell the player all this. For my next project, and certainly for other developers write player focused dialogue early! Obviously be blocking your story at the same time, but the fun detail comes from sitting in some world and immersing yourself in it. I think for a future project I wish that I had the ability to do some of this sooner so that I could then tell the level designer the things that I had discovered about the spaces that they had created and we could go in and add micro-detail to the spaces. I really think that’s the best way to create spaces that feel real is by having a molding back and forth conversation between multiple professionals.

If you are just starting out and you want to try writing, give the tool Twine a shot! Create a small fictional space with some tragedy that the player discovers by simply exploring each room. What signs of life would the people have left in each room? How would those things have been left so that the player can discover them, and put the pieces together.